What is

Partimenti?

After about a decade of teaching and making music with partimenti — and reading everything I can get my hands on, from historical sources to modern scholarship — I’ve noticed that scholars, performers, historians, and teachers tend to use the word partimenti in four closely related ways.

Partimenti can refer to:

A body of purposely unfinished repertoire

A musical practice

A teaching tool

A method of understanding music

These aren’t separate definitions so much as different facets of the same tool. And understanding all four helps explain why partimenti has become such an important part of my own musical life.

Partimenti as purposely unfinished repertoire

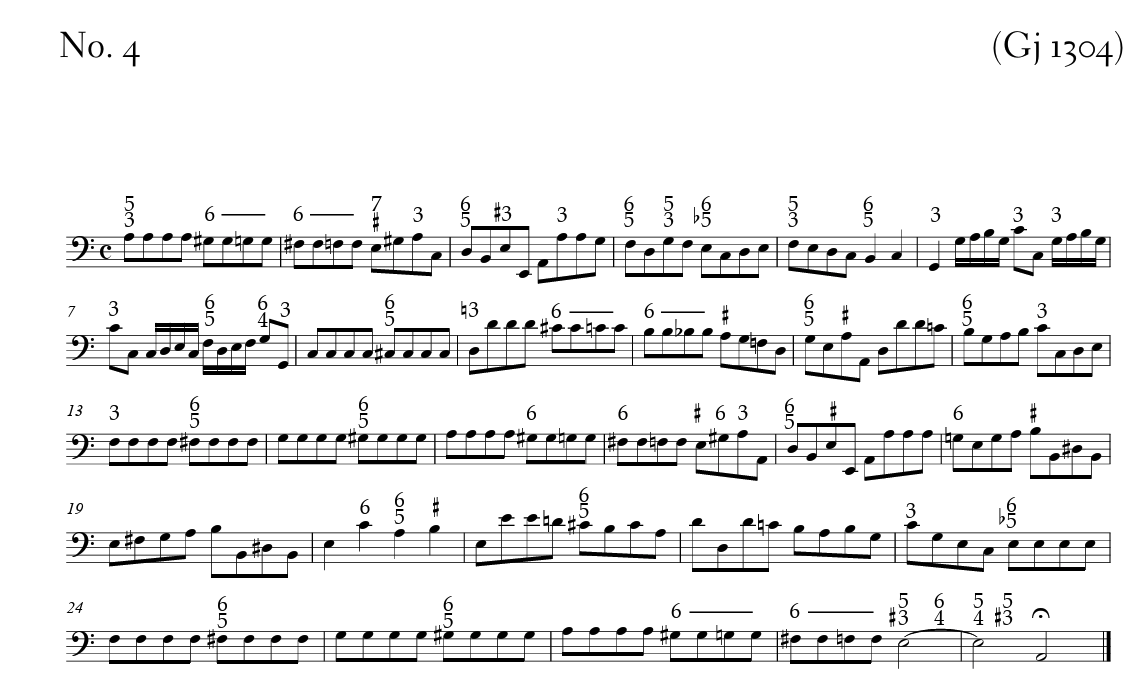

At its most concrete, a partimento is often just a bass line — sometimes figured, sometimes not — intended to be realized, expanded, and completed by the musician.

In archives and libraries around the world there are collections of manuscripts containing little more than bass lines. Some explicitly carry the label partimento; others don’t, but clearly function the same way. These were never meant to be finished compositions. They were invitations — musical starting points that students in training and professionals would bring to life through realization.

I often say a single bass line holds an almost infinite number of realizations. Think of all of the parameters that are avilable — texture, rhythm, register, figuration, style, tempo, articulation, harmonic density, contrapuntal complexity. Each realization can become an entirely new piece.

If you’re curious to explore this repertoire yourself, one excellent starting point is partimenti.org. These are mostly modern editions of classical partimenti. I recommend beginning with Fedele Fenaroli’s collections. Book 3 presents the “rules,” though they can sometimes feel cryptic because partimenti was fundamentally an oral tradition. The written rules were reminders rather than full explanations. Books 1 and 2 include figured basses, while Books 4 through 6 present increasingly complex unfigured bass lines.

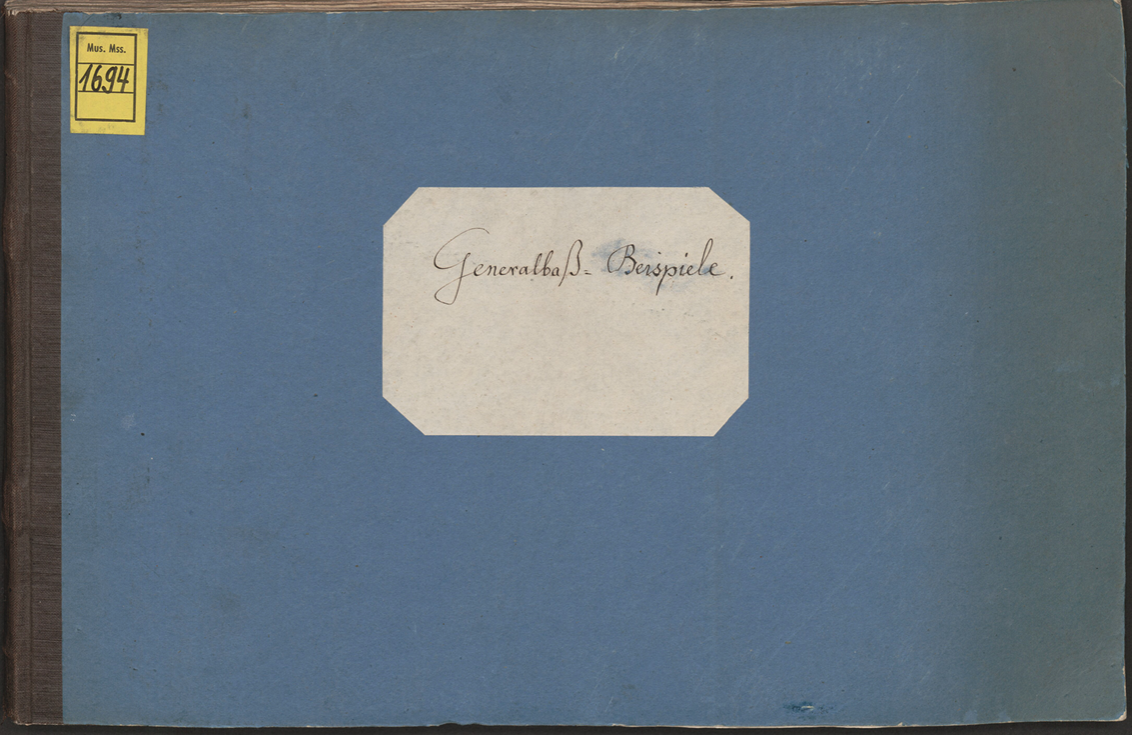

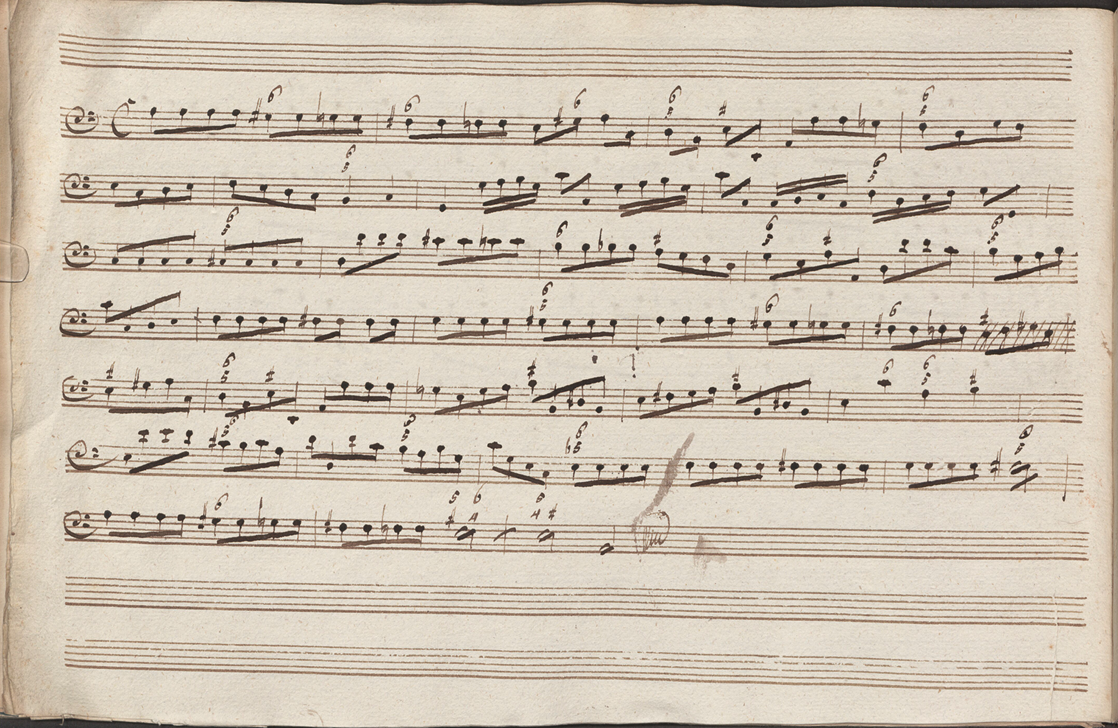

You can also find historical partimenti publications and manuscripts on IMSLP. Personally, I find Fenaroli’s early Ricordi edition from 1847 fascinating, but even more compelling are handwritten manuscripts such as the circa-1825 copy by Georg Weissinger. These handwritten sources give us a glimpse of how this tradition was transmitted — often copied by students themselves into notebooks sometimes called zibaldoni (informal personal compilations of musical material).

Seen this way, partimenti aren’t just historical documents — they’re catalysts for living music. Those seemingly simple bass lines invite us into a tradition where music is not merely read or preserved, but actively created, heard, and reimagined each time a bass line is realized.

Partimenti as a musical practice

Partimenti aren’t just historical artifacts — they represent a living musical practice.

A bass line serves as a catalyst for improvisation, composition, and performance. Through familiarity with harmonic and contrapuntal patterns, musicians generate melody, texture, inner voices, and expressive shape directly from that bass. Each realization becomes a unique act of music making.

Many musicians have encountered something related to partimenti through figured bass or basso continuo practice. Like partimenti, continuo playing involves improvising harmony over a bass line. But there’s an important distinction.

Continuo playing is primarily accompaniment. It supports an ensemble: singers, instrumental soloists, orchestras. The chording instrument plays the bass and fills in harmony while another single line instrument carries the bass alone.

A partimento, by contrast, stands on its own. The player generates a complete musical texture: bass, harmony, melody, inner voices, rhythmic character — creating in real time.

That’s why partimento practice sits at an intersection of improvisation, composition, performance, and understanding.

Partimenti as a teaching tool

Historically, partimenti were central to how musicians were trained.

One fascinating challenge when studying historical partimento collections is that they often begin in the middle of the learning process. Fenaroli’s partimenti assume students already know cadences, some sequences, and the Rule of the Octave — itself a collection of multiple harmonic conventions.

We know from historical accounts that earlier training happened orally and interactively. Students used chalkboards. A teacher or maestro would give a bass line and students would copy it. The maestro then would demonstrate realization, at first basic then increase complexity gradually, and students would copy, transpose, mix, vary, and eventually hold those patterns in their ears, brains, and fingers.

Much of that early pedagogy disappeared because chalkboard exercises weren’t preserved. What survives are the later-stage materials.

Part of my own work has been trying to reimagine those missing beginnings — rebuilding exercises that help musicians develop fluency before diving into historical sources directly.

Crucially, this training emphasized speaking music before writing music. Students learned patterns by ear, through repetition, variation, and experimentation, until those patterns became internalized musical language.

Partimenti as a method of understanding music

This last dimension has been the transformative for my ears.

As an undergraduate, I struggled with ear training. I wasn’t bad at analysis, but listening without notation felt frustrating. Looking back, I realize my ears lacked context. I hadn’t been given a framework for hearing how to listen to music.

Partimenti provided that framework.

Now when I intentionally listen to music, I listen to the bass line. I listen for whether the harmony fulfills expectations implied by that bass, or whether it subverts them. Much of common-practice repertoire relies on recurring patterns — cadences, sequences, the Rule of the Octave — and understanding those patterns makes the music immediately more intelligible. Classical music is drenched in the Rule of the Octave. Once you hear it, you start noticing it everywhere from William Bryd to Mahler, from Gospel Music to Lady Gaga.

Interestingly, when composers deviate from those conventions, those moments often carry special expressive power. There’s a saying attributed to Gabriel Fauré: you don’t have to be a genius in every bar. Much music is built from shared conventions. That’s not a weakness — it’s a language.

Bringing it all together

So what is partimenti?

It isn’t just one thing.

It’s a repertoire of intentionally unfinished music.

It’s a musical practice grounded in creation.

It’s a teaching method that shaped generations of musicians.

And it’s a powerful way of understanding how music works from the inside out.

For a growing number of musicians today, partimenti fills a gap — connecting theory, repertoire, improvisation, listening, and composition into a single, integrated practice.