A Music Lesson from Charlemagne, King of the Franks

Sound Before Sight in History

In my last post, Sound Before Sight, I ended with a simple formula:

Sound comes first. Understanding follows. Notation arrives later as a way of naming and preserving something we already know.

Today, I want to zoom way out in history and show that this idea isn’t new. In fact, it sits at the very root of Western music notation.

Music notation is so ingrained in modern musical life that it’s easy to take it for granted. We assume music is meant to be written down and preserved. We assume that learning music starts with learning notation.

But for most of history, music lived primarily in people’s ears and memories. Really, for most of us, it still does.

Before Notation: Collective Musical Memory

It was the tradition of the Roman Church — what we would now call the Catholic Church — that gave rise to the earliest centuries of Western music notation.

Roman monks and priests sang chants assigned to particular days, feasts, and services. Books contained the words of prayers and hymns, but not the music. There was no need. The melodies were learned through listening, repetition, and communal memory. Where one singer forgot, others remembered. Sound came first, and it stayed alive through repetition and community singing.

The Problem Charlemagne Created

This changed because of a very practical problem.

Around the year 800, Charlemagne, King of the Franks, had recently been crowned Holy Roman Emperor. He was working to unify his vast empire under a common religious practice. His empire included what we now know as France, Germany, the Low Countries, Switzerland, Austria, and northern Italy, with smaller regions extending into Spain.

"Charlemagne, Emperor of the West (742–814)"

Painted by Louis-Félix Amiel in 1839 for the Palace of Versailles. This idealized portrait depicts the founder of the Holy Roman Empire holding a scepter and a globus cruciger, symbols of his absolute temporal and

He wanted the same Roman liturgy spoken and sung throughout his realm. Written texts could be copied and distributed, but music could not. You couldn’t simply ship sound from Rome to distant churches.

To solve this, experienced Roman singers were sent out to teach chants in far-flung places. But now the collective memory was fragmented. A single monk might be responsible for teaching an entire repertoire that had previously been held by a whole community. Inevitably, memories faltered and melodies began to drift. Different churches started singing different versions of what was meant to be the same chant.

The Birth of Music Notation

Faced with this challenge, monks began experimenting with marks on the page. These early signs weren’t precise instructions — they were reminders for melodies the singers already knew. Small dots and squiggles indicated whether a melody moved up or down, or whether notes were close together or far apart.

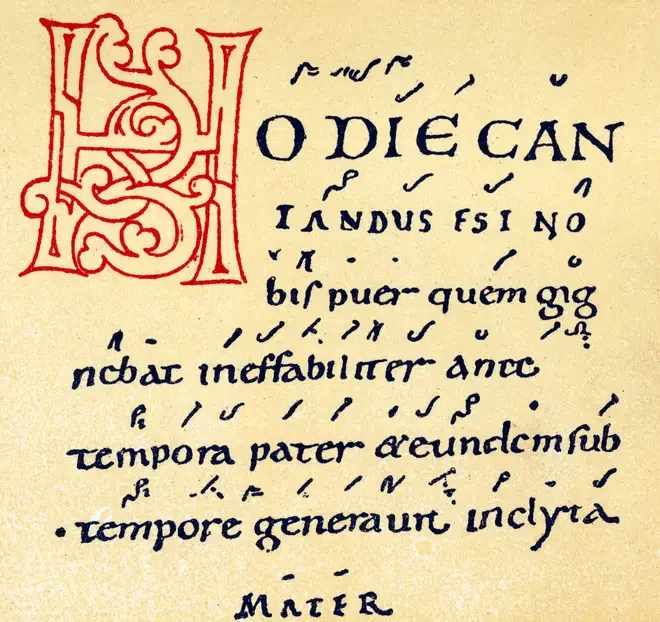

"Hodie Cantandus: 10th-Century Gregorian Chant Manuscript"

A page from the 'Hodie Cantandus' trope by the monk Tutilo of St. Gall (c. 10th century). The manuscript features early staffless musical notation known as neumes, which provided mnemonic cues for the rise and fall of the melody before the invention of the modern musical staff.

Later, a single horizontal line was added as a pitch reference. Much later still, that line evolved into the five-line staff we use today.

What mattered most wasn’t the notation itself. What mattered was that it helped singers remember the sound.

Notation was born not to create music, but to assist memory.

Sound Before Sight (Then and Now)

This is exactly the principle behind sound before sight. The monks did not sing from notation; they sang from memory, ear, and habit. Notation came afterwards as a support — a guide and reminder that helped preserve what already existed in sound.

That lesson still applies today.

Notation is an extraordinary tool, but it remains a tool. Your ears are more musical than your pencil. They’re more musical than black dots on a page — and often more musical than your software. The page should capture and clarify music, not replace the act of making it.

Why This Matters for Partimenti

This is one of the reasons partimenti are so powerful. In partimento practice, music begins with listening and imitation. You play, you listen, you respond. Only after patterns live comfortably in your ears and hands do you name them, analyze them, or write them down.

Writing becomes a way of preserving and communicating something you already understand in sound.

A Simple Order to Remember

So as we continue this journey, keep that simple order in mind:

Make the music.

Understand the music.

Only then, write the music.

Sound comes first. Understanding follows. Notation arrives later as a way of naming and preserving something we already know.