Dear Herr Haydn

Lately, I’ve been reading and thinking about Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) and his early apprenticeship with Nicola Porpora (1686–1768), a renowned teacher from Naples. Porpora had trained at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo, one of the major Neapolitan conservatories where partimenti formed the core of a very practical, hands-on musical education.

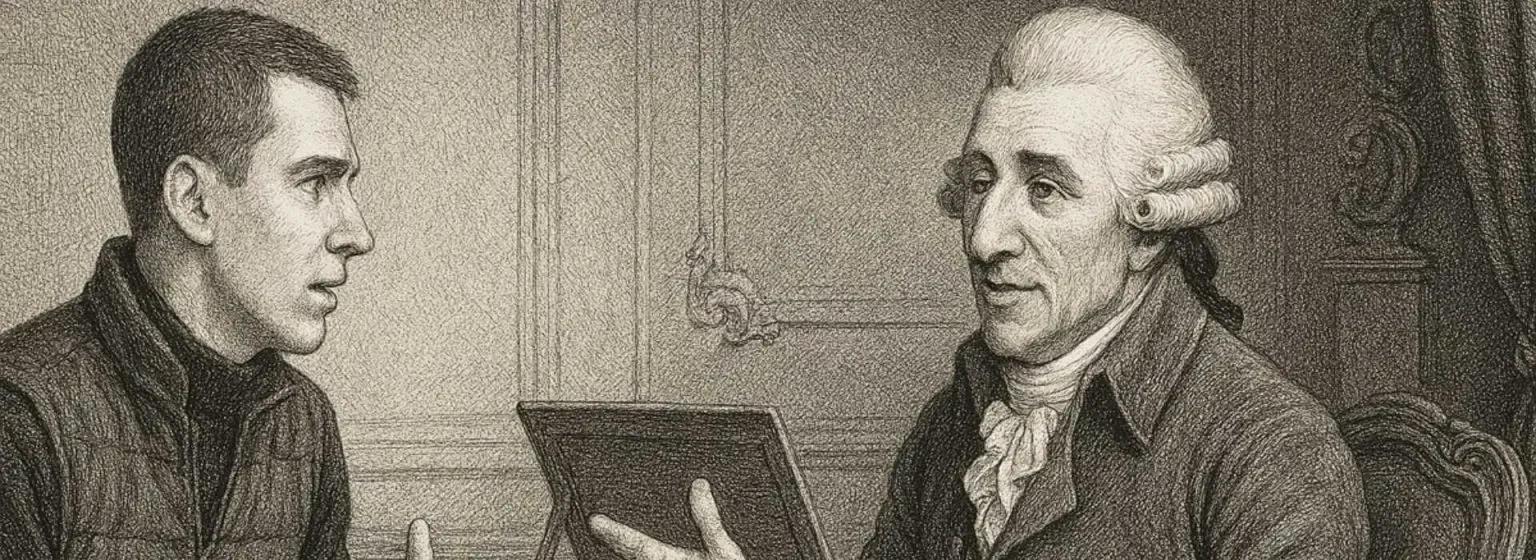

Years later, when Porpora was living in Vienna, he hired a young, struggling freelance musician named Joseph Haydn as his accompanist and valet. Despite the humbling nature of the job, Haydn later credited Porpora with teaching him “the true fundamentals of composition.” High praise from one of classical music’s great architects.

As I read about Haydn, I began imagining a conversation with him — about Porpora, about partimenti, and about where music has gone since his time. The letters that follow are fictional, of course, but the questions are real: what can we still learn from this older way of thinking? And how might someone like Haydn respond to the musical world we live in today?

Letter One: Ian to Haydn

Winnipeg, a Thursday evening, after teaching and before dishes

Dear Herr Haydn,

I hope you’ll forgive the liberty — I’m writing to you across more than two centuries. I’ve been studying a method of teaching that I believe you knew well: partimenti. These bass lines were used to teach harmony, counterpoint, and improvisation — often without lengthy explanations. Just the keyboard, your ears, and the shapes under your fingers.

You once said you learned the fundamentals of composition from Porpora. I wonder if that was what he gave you — those basses, and the expectation that you would make them speak.

Your music has been with me for years. It carries clarity, wit, and purpose. I hear in it a kind of freedom that I suspect grew from deep discipline — music learned through sound as much as through rules.

I would love to know how Porpora taught you.

With respect,

Ian

Letter Two: Haydn Replies

Vienna — or wherever the ear still leads

Dear Herr Campbell,

What a pleasure to receive your letter. I am glad to hear that partimenti still live in some form, and that teachers like you are placing them again in students’ hands.

Yes, Porpora gave me basses — sometimes figured, often not — and told me simply to play. To try, fail, and try again. He did not explain much. He showed, and expected me to learn by doing. He was strict, but he taught me to think musically rather than theoretically. That may have been the greatest gift I received.

May I ask in return: what has become of music in your time? Do people still gather to play? Do children still sing? Has the keyboard changed?

And Winnipeg sounds very cold. I hope your stove is well-fed and your fingers still warm enough to play.

Yours,

Joseph Haydn

Letter Three: Ian Responds

Winnipeg, late afternoon, the piano slightly out of tune after a long winter

Dear Herr Haydn,

Thank you for your reply. Hearing about your time with Porpora resonates deeply with my own teaching. Learning through sound and gesture still feels like the most direct path to musical understanding.

Music is everywhere now. We carry recordings in our pockets — entire orchestras in tiny devices. It’s miraculous, but it has changed how often people make music together. Listening is abundant; participation is sometimes rarer.

Children still sing, though music education competes with many other demands. The piano remains, though electronic keyboards are increasingly common. We even compose using computers — entire symphonies can be written and heard without live performers.

Yet the ear still matters. A well-shaped phrase still moves people. A cadence still satisfies. And when people gather to make music together, it still feels sacred.

Yours,

Ian

Letter Four: Haydn Reflects

Where the air is quiet and no one tunes the violins

Dear Herr Campbell,

How extraordinary to imagine music carried in pockets! And machines that sing.

I cannot say I like the thought that fewer people make music themselves. Perhaps abundance makes us forget the effort creation requires.

Tell me: do your students still learn to listen deeply? Do they feel the weight of suspension and the relief of resolution? Or is everything too fast now?

If they still search for melodies that feel inevitable, perhaps the spirit of the thing survives.

Keep going.

Yours,

Joseph Haydn

Letter Five: Ian Concludes

Winnipeg, the snow melting fast, the piano freshly tuned

Dear Herr Haydn,

Yes — the world is faster. There’s more music than ever, but not always more listening. That’s part of what I try to teach: how to slow down and hear.

With partimenti, I ask students not to label first, but to respond. What does the bass want? Where is it leading? We focus on gesture, tension, and release. It can be messy, but when a cadence feels earned, they know it. That’s how I know they’re learning.

Your letters have clarified something for me: tradition isn’t preservation alone. It’s continuity — a way of thinking passed through sound from musician to musician.

Thank you for reminding me.

With gratitude,

Ian

A Closing Thought

This correspondence is imagined, of course. But the questions are real. What does it mean to teach music when sound is everywhere? How do we train judgment, listening, and creativity — not just knowledge?

In writing to Haydn, I found myself writing to the lineage I work within, and to the future I hope to help shape. Perhaps you’ll find something of your own in these letters — and maybe even write a few of your own across time.