Once upon a time, in the Kingdom of Naples

"Piazza dei Martiri, Naples (c. 1895)"

This vibrant photochrome print, published by the Detroit Publishing Company, captures the historic 'Martyrs' Square' in Naples at the end of the 19th century.

A Musical Tradition Born in Naples

Once upon a time, in the Kingdom of Naples — a land of sunlit streets and lively piazzas — musicians developed an ingenious way to learn, teach, and create music. This method was efficient, effective, and, perhaps most importantly, fun.

Much like children building castles with Lego bricks, musicians worked with musical patterns, combining them in countless ways to create melodies, harmonies, and counterpoint. Their playful experimentation produced fresh music that filled churches, courts, theaters, and public squares.

This tradition is what we now call partimenti.

Learning Music Like Language

In the conservatories of Naples, young musicians learned music much the way children learn to speak. Beginning around age ten, a maestro guided them through listening, imitation, repetition, and gradual invention.

The teacher might play a bass line — a partimento. The student listened carefully, then copied it. The maestro would add an upper voice, then embellishments, then additional layers. Over time, students internalized these patterns, mixed them together, and eventually began inventing their own musical responses.

These bass lines became treasure maps. From them, students could create minuets, church music, operas, or instrumental works. With each new pattern, their fluency in the musical language grew.

A Tradition That Shaped Great Composers

For generations, this oral tradition produced extraordinarily capable musicians. Many individual teachers’ names have faded into history, but their influence remains everywhere.

Among composers shaped by this tradition are:

Alessandro Scarlatti, J.S. Bach, Handel, Domenico Scarlatti, Porpora, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, and Verdi.

Partimenti training helped make their improvisational fluency, compositional skill, and harmonic understanding possible.

From Naples to Paris

As political and cultural life shifted across Europe, these teaching methods spread. In France, the Conservatoire de Paris, founded in 1795 after the Revolution, adopted many Italian pedagogical practices.

Luigi Cherubini, trained in Italy, led the Conservatoire and helped shape its curriculum. Generations of musicians studied harmony through bass patterns and practical musicianship. Composers such as Saint-Saëns, Gounod, Ravel, and Debussy emerged from this environment.

The tradition evolved but remained rooted in listening, improvisation, and pattern recognition.

Decline and Disappearance

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, musical culture began to shift. Written notation, formal theory instruction, and new stylistic directions gradually displaced improvisatory training.

Migration, modernization, and especially the upheaval of World War I disrupted conservatory traditions. Oral transmission became harder to sustain. Partimenti faded from mainstream pedagogy, surviving only in fragments.

Nadia Boulanger and the Thread That Continued

One remarkable teacher helped preserve aspects of this tradition: Nadia Boulanger.

Teaching in Paris, she passed on practical harmonic training to generations of students from around the world, including Lili Boulanger, Aaron Copland, Quincy Jones, Leonard Bernstein, and many others. Through her students, elements of partimenti thinking quietly shaped twentieth-century music.

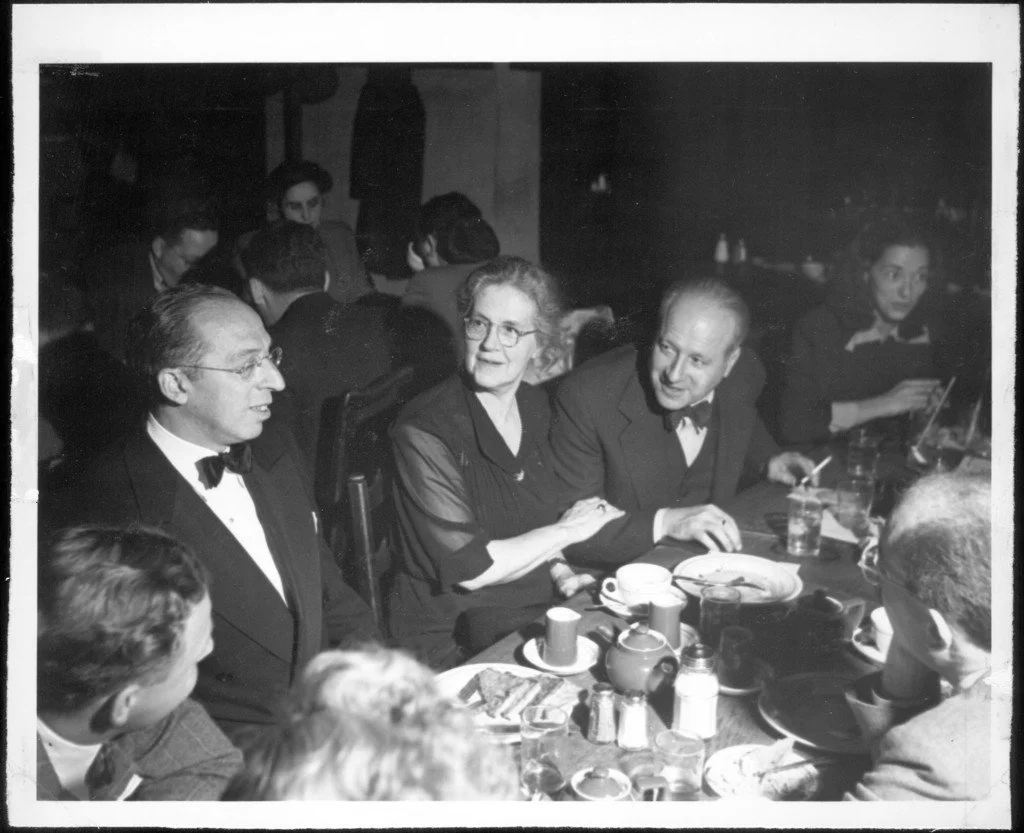

"A Reunion of Masters: Nadia Boulanger with Pupils in Boston (1945)"

Seated from left to right at the Old France restaurant are Irving Fine, Aaron Copland, Nadia Boulanger, and Walter Piston. This historic gathering brought together the legendary French pedagogue with several of her most distinguished American students, whose work she profoundly influenced during their formative years in Paris. Photo from the Library of Congress.

Rediscovery in the Modern Era

In recent decades, scholars and musicians have begun rediscovering partimenti through historical manuscripts, treatises, and pedagogical exercises. What once seemed obscure is increasingly recognized as a powerful teaching tool.

Musicians today are integrating these methods again, reconnecting with improvisation, listening, and creative fluency.

What Neuroscience Tells Us

Modern neuroscience supports what these historical teachers already understood: improvisation strengthens memory, creativity, and learning.

When musicians improvise, brain networks associated with creativity and problem-solving become highly active. Learning through patterns and listening reinforces memory pathways and speeds skill acquisition.

Partimenti naturally fosters these processes.

Learning Music Like We Learn Language

Partimenti closely mirrors language acquisition. Students first listen, then imitate, then experiment, and eventually create independently.

This leads to deeper fluency than learning exclusively from notation. Harmony becomes something you hear and feel, not just something you analyze.

Beyond Historical Style

Although rooted in Baroque and Classical traditions, partimenti principles transcend genre. Pattern recognition, harmonic fluency, and improvisational thinking can inform jazz, film scoring, popular music, and contemporary composition.

Many musicians find that partimenti bridges stylistic boundaries rather than reinforcing them.

Performance, Composition, and Collaboration

Historically, partimenti training supported both performance and composition. Musicians learned to improvise cadences, ornamentation, and accompaniment, leading to more expressive interpretations.

Group learning was also central. Students listened to each other, responded musically, and developed ensemble awareness — skills still essential today.

Unlocking Creative Possibilities

The revival of partimenti is more than historical curiosity. It represents a return to a deeply human way of learning music — listening first, experimenting freely, and understanding from the inside out.

By reconnecting with these practices, we don’t simply recreate the past. We gain tools for more fluent performance, richer composition, and more creative musical lives today.

And perhaps most importantly, we rediscover how joyful making music can be.